Published: 09:26 AM, 12 October 2025

The Forgotten Commander of Netaji: Ananga Mohan Dam and the Lost Legacy of Sylhet’s Revolution

Sangram Datta:

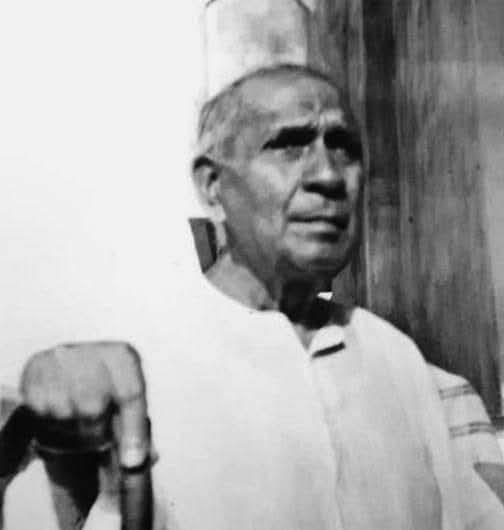

In a quiet neighborhood of Sodepur, north of this sprawling city, an aging man once lived a life far removed from the tumult of his youth. Neighbors remember him as polite, reserved, and always reading. Few knew that he had once stood beside Subhas Chandra Bose, led protests that shook the British Empire, debated with Sardar Patel, and spoken face to face with Mahatma Gandhi.

His name was Ananga Mohan Dam, a revolutionary from a small village called Sadhuhati in South Sylhet — now across the border in Bangladesh. For decades, his story lay buried in fragments of memory, old letters, and fading government records. Yet, his life embodies the complex, often untold struggle of India’s eastern frontier during the freedom movement — a struggle marked by idealism, exile, and betrayal.

A Rebel Born in a Time of Upheaval

Ananga Mohan Dam was born on December 10, in either 1890 or 1893, into privilege — the son of Rai Saheb Abhaya Kumar Dam, a zamindar of the Sataro Sati Pargana and Baurbhag regions in what was then South Sylhet of Assam Province in British India.

The elder Dam was a respected man who quietly rejected the colonial honors bestowed upon him by the British. His home was one of learning, culture, and quiet defiance. When Bengal was partitioned in 1905, the nationalist fervor that gripped Calcutta soon reached Sylhet, where young Ananga was studying at Raja Girish Chandra School.

At the Govinda Charan Park and Ratanmani Loknath Town Hall, he watched towering figures of the Swadeshi Movement — Bipin Chandra Pal and Dr. Sundarimohan Das — ignite the imagination of the people. At just 13 years old, Ananga joined the Swadeshi volunteers. “From then on,” wrote one contemporary, “the idea of a free India had taken root in him like faith.”

Scholar, Philosopher — and Secret Revolutionary

Brilliant and disciplined, Ananga passed the Calcutta University entrance examination in 1909 with a scholarship — a remarkable achievement given his growing involvement in anti-British activities.

After his father’s death, relatives expected him to manage the family’s vast estate. Instead, he left for Calcutta to pursue higher education at Presidency College, the intellectual hub of Bengal’s awakening.

There, his circle of friends read like a future hall of fame: Satyendra Nath Bose, the physicist who would later lend his name to the boson particle; Gyan Chandra Ghosh, a noted chemist; and Pulin Bihari Sarkar, a nationalist educator.

In the Eden Hindu Hostel, Ananga was drawn into the clandestine network of the Jugantar group, one of India’s earliest revolutionary organizations. The group’s motto was simple and uncompromising: “Arms and action.”

By 1915, the British police had marked him as a “person of interest.” He was followed, interrogated, and threatened — yet he remained undeterred. That same year, on December 10, the students of Presidency College held a farewell for Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose before his overseas tour. The opening song, composed by Ananga, filled the hall with patriotic fervor.

When Bose himself delivered a speech invoking the spirit of scientific and national awakening, Rabindranath Tagore, who was in attendance, nodded in quiet approval.

Within months, Ananga and his friend Subhas Chandra Bose would both be expelled from Presidency College — a punishment for “disruptive nationalist activities.”

From a Bookshop to a Jail Cell

In 1914, still pursuing his dream of becoming a barrister, Ananga opened a small bookshop at 1 Cornwallis Street in north Calcutta. The shop was intended to pay for his legal studies. Instead, it became an informal center of nationalist exchange — a place where students, intellectuals, and young revolutionaries met, debated, and planned.

Two years later, the British raided the store. Dam was arrested under the Defence of India Act, accused of aiding sedition. He was sent to Presidency Jail, confined in the “Political Cell,” and later interned in Assam under a detention order.

“He used his own earnings to support poor students and revolutionaries,” recalled a contemporary memoir, “and when he had nothing left, he gave his health.”

By the time of his release in 1920, after the end of World War I, he was frail but unbroken.

A Delegate, a Commander, and Gandhi’s Messenger

In September 1920, representing Sylhet District, Ananga attended a special session of the Indian National Congress in Calcutta, presided over by Lala Lajpat Rai. It was here that the historic resolution for the Non-Cooperation Movement was passed.

When the Prince of Wales visited Calcutta soon after, protests filled the city. Dam, as the commander of the volunteer corps, maintained discipline amid chaos. When top leaders like C.R. Das and Subhas Bose were arrested, Deshbandhu Das entrusted him with leadership of the volunteers — a task he carried out so effectively that Mahatma Gandhi sent him a personal letter of blessing.

Later, Pandit Shyam Sundar Chakraborty dispatched him to Delhi to consult Gandhi on the proposed No-Tax Movement. Meeting at Dr. Mukhtar Ahmed Ansari’s residence in Daryaganj, Gandhi discouraged the tax boycott but urged Ananga to devote his energy to rural reconstruction, education, and communal harmony.

Dam obeyed. For the next two decades, he worked across greater Sylhet, organizing village schools, campaigns against untouchability, and programs for Hindu-Muslim unity.

The Statesman from the East

In 1943, amid the flames of the Quit India Movement, Ananga Mohan Dam was elected to the Central Legislative Assembly in Delhi from the Barak-Surma Valley. Under Minister Gopal Swami Ayyangar, he became an advocate for the development of Assam and Sylhet, focusing on education, infrastructure, and civic reform.

But history was turning fast — and harshly.

As India’s partition loomed, Dam watched with alarm as political currents in Assam and Delhi began to shift. Certain Assamese elites and Muslim politicians, wary of Sylhet’s Bengali-speaking majority, sought to detach it from Assam altogether.

Dam foresaw the danger.

A Voice Against Partition

He urged the Congress leadership to keep Sylhet under Central Administration until a fair settlement could be reached. In one recorded meeting, Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel dismissed his plea:

“Sylhet being such a far-off place from Delhi, almost in the North-East Frontier, and you are saying that Sylhet should be kept under Central administration? Dam, your idea is nonsense.”

Dam’s quiet reply would prove hauntingly prophetic:

“Sardarji, you shall have to revise your opinion.”

When the Sylhet Referendum was announced in 1947, Nehru and Mountbatten, seeking to appease Jinnah, declared that tea plantation laborers — mostly migrants — would not be allowed to vote.

Dam, leading a delegation of Sylheti representatives, traveled to Delhi to protest. His appeals were ignored.

Desperate, he proposed an alternative vision: the creation of a new province, “Purvachal”, encompassing Sylhet, Cachar, the plains of Tripura, and Manipur, with support from the Maharaja of Tripura. Patel privately conceded his mistake but said the decision was now “in the hands of the Viceroy.”

Even Gandhi, when approached, remained silent.

Exile and Silence

Betrayed and heartbroken, Dam returned to Sadhuhati just two days before India’s independence. Friends warned him that the Muslim League government might arrest him.

On the dawn of 14 August 1947, he offered prayers before his household deity, donned a simple dhoti, and walked away — leaving his ancestral home forever.

He would never again set foot in Sylhet.

The Final Years

In post-independence India, Ananga Mohan Dam withdrew from public life. He lived quietly in rented houses at Lower Circular Road in Park Circus and later Ashoknagar (Habra).

Only in 1965, when his eldest son Ashish Kumar Dam, a government officer, bought a modest flat at Sodepur, did the family find stability.

The revolutionary once feared by the British died almost unnoticed on January-6, 1978.

No memorial marks his grave. No statue bears his likeness.

Yet, in the long shadow of India’s freedom movement, his life stands as a testament to those who fought without reward — men and women whose courage outlasted recognition.

The Forgotten Frontier

Today, as borders and identities continue to shape South Asia, Ananga Mohan Dam’s story reminds us of a time when the idea of India stretched beyond maps — when conviction mattered more than geography.

He was, as one historian later wrote, “a man who spoke truth to power, even when truth was unwelcome.”

And though history may have forgotten his name, the quiet village of Sadhuhati, now on the other side of the border, still remembers — the home of a scholar, a rebel, and the forgotten commander of Netaji.